| Adel Al-Yousifi is a Kuwaiti businessman, photographer, publisher, and social reformer. He awoke in London on the morning of August 2, 1990, to hear Iraqi troops had invaded his country. As days passed and Iraq showed no sign of withdrawing, Al-Yousifi determined to participate in his compatriots’ quest for Kuwait’s liberation. He found his niche as a volunteer photographer for the Free Kuwait Campaign run out of the National Union of Kuwaiti Students’ headquarters on Porchester Terrace. During the 7 months of the occupation, he recorded the FKC’s activities in more than 8,500 photos. From this collection, he culled several hundred photos for a book he published in 1997, Free Kuwait Campaign: a Testimony from London. He launched this website in 2012 to expand on the book with more photos, more text, and videos. After returning to Kuwait in March 1991, he spent 8 months photographing the ravaged country. This effort resulted in 2 books and in the Evidence website. |

What was the Free Kuwait Campaign (FKC)? It was the immediate response of the Kuwaiti people outside their homeland to the Iraqi regime’s invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990. It encompassed all the activities of these Kuwaitis to restore their legitimate government. It included persuading the citizens of the world to support use of military force to liberate Kuwait after the Iraqi regime refused to leave peacefully. It included creating solidarity among hundreds of thousands of exiled Kuwaitis, offering sustenance to those in financial need, and giving hope to those inside Kuwait that everthing possible was being done to end their ordeal. It included the efforts of our many foreign supporters. It stood for all that was right and it was against all that was wrong. It lasted 7 months till Kuwait regained its freedom on February 26, 1991. Though the campaign had different titles in different nations, the goal was exactly the same. This website’s main focus is on the activities in London, UK, because it’s where I was living during the occupation of my country and where I used my camera to document most of the events of that momentous time. Who was in charge of the FKC in Britain? The National Union of Kuwaiti Students for the UK & Ireland, part of the worldwide students’ organization known as NUKS, was the British campaign’s focal point. By the invasion’s second day, several of their graduate students who held office in NUKS or had activist experience formed an executive group called the Kuwaiti High Committee to coordinate all responses to the crisis and to act as liaison with other national and international organizations. Also named as KHC members were several non-student activists and an official of the Kuwaiti Embassy. FKC headquarters was the NUKS building at 41 Porchester Terrace, just northwest of Hyde Park in London. Why did you create this website? I didn’t want the era of the Free Kuwait Campaign to be forgotten. It’s part of Kuwait’s history. After liberation, for years I waited for the government to acknowledge the efforts of the groups in the UK, UAE, and many other nations around the globe. There was nothing – no monument, no publication, not even a tea party. No one got credit for all the sacrifice and hard work, and as time passed the danger grew that their contribution wouldn’t be remembered. My first response was to publish a book of photos in 1997 called Free Kuwait Campaign: a Testimony from London. I sent 500 free copies to the Ministry of Education for distribution to school libraries. As the 20th anniversary of liberation was approaching, it became clear that a website was the best way to keep this era alive. I was dissatisfied with the book. I had not joined the FKC right at the start and I had taken photos with no intention of creating a book, so the coverage was random. I missed many activities, which means the website does not represent the FKC’s entire history but rather my personal view of the FKC. Nevertheless, the website contains more than the book especially since I opened it to other contributors. How did you come to be FKC’s photographer? As soon as I heard of the FKC, I determined to pitch in. I kept offering to do Media Committee work, but, since I had no particular writing skills or public relations experience, nothing ever happened. It was also clear the committee’s office space in the Porchester Terrace basement was limited. I used to show up and help with small chores. Gradually the members came to trust me. After photographing the first major march on September 9, I considered myself FKC’s volunteer photographer without formally being hired. Were you the only FKC photographer? No. Omar Buhamad was the official photographer and perhaps there was one other. I was the unofficial one. Others also made audio and video recordings, some privately and some government sponsored. The KHC offered to reimburse me and have me be an official photographer, but I declined. My reasons were that I wanted autonomy to go where I pleased and that I wanted to retain ownership of my photos. Fortunately I could afford the cost so I paid personally for all my photography. What kind of events did you photograph? Indoors I photographed public meetings, ceremonies, performances, committee members at work, and diwaniyas. Outdoors I photographed the major marches and rallies from near and far, gatherings and speakers in Hyde Park, Kuwaiti men and women leaving London to assist the coalition forces, and ceremonies. How many photos did you take in London? I took more than 8,000 photos from early August 1990 to mid-March 1991. For the website, I chose about an eighth of these. Besides photos, do you have other FKC mementoes? I kept documents like leaflets, newsletters, and magazines. I kept memorabilia like campaign buttons, stickers, pens, posters, postcards, and the FKC’s official tea mug, umbrella, and sweatshirt. Did you perform other kinds of work on the campaign? I helped to create the placards before marches. I performed small chores for the Media Committee, such as making tea. Every night from 8 to midnight I attended the Kuwaiti People’s Committee diwaniya at Dorset Square. Once I paid to bring Fahmi Huwaidi, a famous Egyptian author and political columnist, to address the diwaniya and deliver a lecture to a wider audience. I also commissioned and funded the design of a Free Kuwait postcard. Was this the only diwaniya associated with the FKC movement? At first it was, but later the Kuwaiti High Committee organized its own daily diwaniya on George Street. After this, I went back and forth to photograph both diwaniyas especially when they had notable guests.

Were there other Free Kuwait groups in London besides those overseen by the Kuwaiti High Committee? Yes. For instance, volunteer groups like the Kuwaiti People’s Committee and the Kuwaiti-British Friendship Committee were not under the KHC. The Kuwaiti government had organizations, such as the Association for Free Kuwait, with paid staff. The AFK and KHC held some joint events, most notably on November 2. Several US public affairs firms, such as Hill & Knowlton, also paid by the government, had a presence in London, but we didn’t interact with their staff. Did these groups differ? Yes. We were the most visible and we made the most noise. We organized marches and rallies, issued weekly and then daily publications, and got the lion’s share of the news media’s attention, first in the UK and then worldwide. Did anyone’s efforts stand out more? The members of those committees I knew best had a synergy that allowed them to be effective without a formal hierarchy. Everyone rowed the boat in the same direction. As for effort, the dedication of Ali Al-Mulaifi impressed me the most – the long hours, his talent as a coordinator, his savvy in front of the news media, and his courage in joining the coalition forces as an interpreter. How did you feel about non-Kuwaitis participating in the FKC? Words can’t convey my gratitude. Without worldwide public support for a military solution to our predicament, Kuwait would not have regained autonomy. It’s mean-spirited to second guess their motives. To help us, some people made big sacrifices – financial and otherwise – by putting their lives on hold for months to be part of the FKC’s daily activities. Even those marching with us only once contributed. Kuwait wasn’t their country, yet they made our crisis their cause. Which non-Kuwaitis do you remember best? Michael Lorrigan, there from the very start, stands out in my mind for his utter commitment. He helped define the Media Committee strategy, acted as mentor to its staff, participated in all its daily activities, gave us the Free Kuwait name, created the FKC logo with some refinement by Ali, and spent more than a month abroad to enlist American support. I recall Gary Eales too for his political role. He traveled all over the UK with Kuwaiti diplomats and officials, and also to Europe. He arranged for participation in debates and meetings. Both contributed far more than I can mention here. And not to be overlooked is John Lewinton, who joined our cause right after his ordeal as a hideaway in Kuwait was over, and the hard work and dedication of Carolyn Tshering and so many others. Did working on the FKC involve risk? We took precautions after Special Branch warned us about danger from Iraqi intelligence agents. Round the clock security guards were hired, deliveries were Xrayed, visitors were searched and vetted, a panic button was installed behind the reception desk, and the windows were taped. Media Committee members especially had a lot of public visibility so they protected their identities by using pseudonyms and keeping travel arrangements confidential. You commissioned an artist to create a Free Kuwait poster. Why? For Christmas, I intended to write to my company’s business partners in other countries, such as Japan and Italy, to tell them I was OK and business would resume after liberation. With this letter, I wanted to enclose a postcard with a Free Kuwait theme. Abdulmohsen Sheshtar was an old friend and talented artist so I asked him to design the card. His design was large to make a statement – an oversize card of 21 x 15 cm. I printed 10,000. Having these cards gave me confidence in the outcome of the crisis. I mailed them to friends and their responses boosted my morale. I sent a few thousand cards to our embassies in the US, France, Egypt, and other nations. I provided the cards to the FKC committees. All this was done entirely at my expense. Why were you and so many Kuwaitis in London on August 2, 1990? Kuwaitis travel abroad in summer when it’s hot, humid, and sometimes dusty. Temperatures can soar to 50ºC (125ºF). Most Kuwaitis go to Egypt, Lebanon, or London, but some go to continental Europe, Turkey, or the Far East. In 1990 some Kuwaitis were in London on vacation, but also many arrived during the occupation. My mother, my family, and I had been in the US in July. On our way back to Kuwait, we stopped in London for few days as two of my sisters and their families were there. Then the invasion occurred and we were stranded. How did you feel when you heard Iraq had invaded Kuwait? It was a shock for everyone, but, for people outside Kuwait – and I was one of them – it was like being caught in an unbelievable bad dream. We hadn’t heard all the threats that Saddam had made, though at times we heard rumors or a bit of American news. I would then call home to talk to one of my two brothers and tell him what is on the news. His always answered not to worry, it was not serious. Well, it was serious. It took me about 10 days to realize the invasion was not a dream. How did you learn of the invasion? My sister’s husband Abdulnabi Jamal brought the news. He had seen it on TV. We then phoned Kuwait and confirmed it. What was your greatest fear when you heard all of Kuwait was occupied? I felt no fear at first. Iraq had come to the border before. Saddam wanted money and attention. it was just blackmail and a desire to be pampered. After the Arab nations protested and Kuwait erased some of his debt, he’d withdraw. Lebanon was the first Arab nation to protest. Iran was the first non-Arab nation in the Middle East to protest, then others followed. I began feeling fear when Saudi Arabia was silent. After 3 days, Saudi Arabia finally denounced the invasion. My initial feeling returned. Now Saddam would withdraw. When he did not, I began fearing that there may not be a peaceful solution and that, to liberate Kuwait, force would be needed and many casualties would be the result.

Did you expect the invasion to last only a few days or weeks? Yes. Many people did. First we thought Saddam wanted to show his power to give him the upper hand in negotiations. Then we thought he wanted money and, as soon as our government gave him some, he would leave. But the more days passed, the more we felt disappointment and dread. When the coalition nations started sending troops to Saudi Arabia, we knew the time for liberation was coming though not exactly how soon. When Saddam formally annexed Kuwait in August, did you fear it was permanent? At no time did I think it was permanent. The only question was how long the occupation would last. Were close relatives in Kuwait during the occupation? Most of our relatives were in Kuwait on August 2. About half of them left Kuwait during the first weeks and some got out after a month or so. They left first through Iran, then to the UAE. Some stayed in the UAE and others joined us in London. They left with forged IDs that gave them other nationalities to make it easier to flee. The forgeries were “official,” that is, they were obtained from the police or army and stamped by government ministers. Both of my brothers and one of my sisters remained in Kuwait. During the occupation, how much contact did you have with people inside Kuwait and who were they? After the first few days, the phone lines went down. Some people who escaped brought news orally and smuggled out letters and tape recordings. Messages from my brothers said don’t worry, we are OK. I worried anyway. Were they really OK or saying this only as comfort? My younger brother Aref would drive to Baghdad to phone from there, but, during the occupation’s last 2-3 months, that communication was cut. While you were in London, did you know your home had been looted and your family business looted and vandalized? At the beginning, my home like many homes was looted. All my cameras and electrical goods were stolen. Then my brother, who was my next door neighbor, allowed some people to live in my house. Many Kuwaitis whose home had no basement moved into a home with a basement due to fear of Saddam using chemical bombs. These people – I do not blame them – damaged my home by nailing wooden planks to all the doors and dripping candle wax on all the floors and rugs, some of which never came off. Candles were needed because there was no electricity. My home was also used to shelter a boy sought by the Iraqis. Three boys who were members of the Resistance were captured and shot. One survived and escaped. His family pretended he had died of his wound and arranged a fake mourning. The Iraqis never found him. He is considered to be a living martyr. Were you in London during the entire time of the occupation? Yes, except for one trip to Dubai during the 2nd week of December. I went there to visit my father and, while in Dubai, I took photos at a diwaniya of Kuwaitis discussing ways of opposing the occupation. Before the invasion, did you admire Saddam Hussein? No! Most Kuwaitis did admire him, but I and many other Kuwaitis did not as for years we had heard and believed the stories about Saddam’s brutality. Why were the Iraqi troops so brutal in Kuwait? They were brutal because they had a brutal ruler. Brutality was their way to rule Iraq for decades and they just continued that in Kuwait. Also, they were not used to defiance and they did not think Kuwaitis would resist them. When Kuwaitis did resist and did give them a hard time, they became even more brutal to scare people. Did the invasion change the way you see people? My view of humanity is unchanged, but my ideology, like the notion of Arab and Muslim unity, has been jolted. The invasion made many Kuwaitis – and I am one of them – realize that to have security we must tie our relationships to all people of the world and not only to Arabs or Muslims. While in London, did your feelings about the Iraqi people change? No. My feelings about people and regimes are separate. I see goodness in all humanity including Iraqis. Governments are a different story. Saddam brutalized his people for 3 decades and brought out the worst in them. To go against his policies was life threatening. Iraq had secular and religious opposition leaders outside the country who came to London to support Kuwait, and we welcomed them. There were Iraqi soldiers in Kuwait who deserted. When caught, they were executed. Did anything about the events of 1990 and 1991 feel good? Yes. I felt good about the support from the international community, not just from governments but also from individuals. When we marched in London to protest the invasion, people of many nationalities joined us. I was proud of the many ways that Kuwaitis inside the country resisted the illegal regime and of the many ways that Kuwaitis helped each other after liberation. How did you feel on January 17 when you heard Desert Storm operations had started? At first I was happy. It was not a surprise. We didn’t know exactly when the attack would start, but rumors from Kuwaitis close to the Saudi government leaked out. By January 16 we knew the attack was hours away. My next emotion was fear. How many would die – how many Kuwaiti civilians, coalition soldiers, and Iraqis running for their lives?

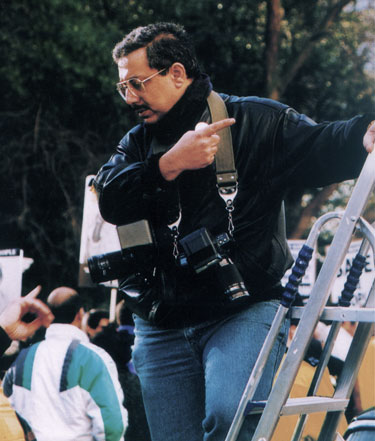

Foreigners were going to die liberating Kuwait. Do you think enough Kuwaitis joined the military to share the danger? Did you try to join? From the first week, many Kuwaiti men, including my brother-in-law and I, went to the Embassy to sign up for the military. It was our duty to do so in a national emergency. Like all able men, we had received standard military training. At the Embassy, we encountered confusion. Our government had vanished. The crisis was bigger than what Kuwaitis could handle on their own. We tried to sign up several times, but nothing happened. The FKC started a Sports Committee to help young men get in shape for battle. Later we heard the coalition forces didn’t want to fight beside non-professional soldiers. Kuwaiti men desiring to do more went to help the coalition forces as civil engineers and interpreters, while Kuwaiti women joined the Red Crescent Society as nursing aides. How did you feel on February 26 when you heard Kuwait had been liberated? I can’t explain it. An overwhelming mixed feeling – euphoria and dread. I held my breath for a long time as I waited to know who had lived or died. Were my friends dead? I braced myself for bad news. Then we learned the death toll was relatively low for such a large-scale military operation. I exhaled and felt my life returning. Next I started reliving all the emotions of the months in London. One day your money is worth £2 to the dinar, the next day it is zero. One day you are a citizen of Kuwait, the next day your country has disappeared. After liberation, when did you leave London? My family and I left London around March 11 for Dubai. From there I went alone to Saudi Arabia. it was still hard for civilians to enter Kuwait, so I bought a small truck and filled it with food and electric generators. This allowed me to cross the Saudi border into Kuwait on March 24. At last my exile was over. What conditions did you expect to find when you returned home? From the start we knew businesses were being looted. I didn’t hear about theft or damage to my home or the homes of friends and relatives till I returned. I wasn’t worried about my home. Both my brothers were in Kuwait to look after it. My concern was, if my home was being looted, that my brothers might act without thinking and get hurt doing something heroic. Did you discover anything new when doing research on the website? Yes. I found people had engaged in more activities and work than I was aware of. But mainly it was about rediscovering old friends and reawakening long- forgotten memories. I now speak to and see people with whom I have not been in touch for 20 years. I learned more of their individual contribution to the FKC and of what they recall about their colleagues. Since those days in London, I see how far they have journeyed in life and I have found them residing across most continents – North America, Europe, Africa, and southern Asia. Do you plan to expand the website? Yes. My camera and I couldn’t be everywhere at once. Efforts of many Kuwaitis and their supporters have not yet been recorded for posterity. I am inviting people who have photos, memorabilia, documents, and videos of interest to please contact me for possible inclusion in the site. I also hope to hear from people who recognize the FKC participants whom we have not yet identified. After 20 years have passed, recalling everyone’s name was not possible. Was the FKC acknowledged during the celebration of the 20th anniversary of liberation ? In a small way, yes. An exhibition about the FKC was on display for 4 days from February 16-19, 2011, at The Avenues, Kuwait’s largest shopping mall. Also for the occasion, Dr. Othman Al-Khadher published a book, Heroic Acts, about the history of the FKC. I see this as the start of increased recognition. What led you to photography? When studying at a South Carolina university in the 1970s, I took an course in photography. The professor said I had talent and urged me to major in it. But my father wouldn’t allow it. He expected me to join the family business. He was also being practical. In Kuwait, then and now, photography is not a career. You can’t earn enough for it to be a fulltime job; it’s expensive even as a hobby. Artistically your imagination is limited – no modeling or nude photography, and most of the landscape is an uninspiring dull flat desert. Contemporary art was not accepted in the 1970s and people’s tastes were very old-fashioned. After college in the US and my stint in the Kuwait army, I spent the next decade concentrating on my business career. But I loved photography and never let it go. I became a critic for friends. On many days, I left the office to seek places to photograph. During this time in the 1980s, I built a small studio and lab at home to experiment with lighting. My work was mainly in black and white. But what I perceived as a lack of technical skill haunted me. I had not taken advanced courses. I felt my understanding of lighting was weak and this held me back. The invasion changed all that. During mid-1990 to early 1991 when stranded in London, I began taking photos daily for the FKC. This forced me to acquire better lenses and to carry at least one camera at all times (which I still do). It took a month or two for my eye to improve, and then I noticed that my shots were better. Once back in Kuwait, I made it my mission to record the damage. I took photos daily for 8 months; the result was a collection of nearly 15,000 negatives and slides. After this, I took photography seriously. My photos from March-November 1991 document the damage in Kuwait and form the basis of my book The Evidence, several art gallery exhibitions on “The Evidence of Malice,” and the website www.evidence.org.kw that I launched on February 26, 2011, the 20th anniversary of liberation.