| About This Site Kuwait Invasion: the evidence is a documentary website.The Introduction section contains a 22-page photo essay summarizing the impact on Kuwait of the Iraqi military invasion, occupation, and retreat during August 1990 through February 1991.In the form of nearly 1,200 photographs arranged by geographical region, the Gallery presents detailed evidence of the massive damage Kuwait sustained and offers a photo tribute to the lives claimed by the invasion.Click Overview for a brief narrative on the different types of damage sustained in each of Kuwait’s five regions (South, Coast, City, Suburbs, and North) and for a look at the names and faces of the many people from varied nations who perished due to the invasion during Kuwait’s seven-month ordeal.To find photos on specific subjects, such as firefighters, fishing boats, hotels, land pollution, oil pipelines, Seif Palace, schools, stadium, or weapons, type one or more words into the SEARCH GALLERY box.All photos in the Gallery regions are from March through November 1991, with a few whose numbers are marked with “A” linked to a comparison of the same scene in 2010 or 2011. (Visit Recovery to see all the before/after comparison photos in one section.) The photos in Human Cost are from 1990-1991 in London and 1991, 2010, and 2011 in Kuwait.To continue with the Introduction, please click on the forward arrow ( > ) at the top of this column. |

The FKC “Stop the Atrocities” March

On December 2, 1990, thousands of Kuwaitis and supporters from around the globe marched in silence from London’s Hyde Park to a rally in Trafalgar Square.

| The Free Kuwait Campaign Kuwaitis at home and abroad awoke on the morning of August 2, 1990, to the news that Iraq had overrun their country and, within a week, to the news that their nation had vanished. Their immediate response: resistance at home and appeals abroad for help to oust the invaders. Though as yet nameless, the UK’s Free Kuwait Campaign began within hours of the invasion when a few Kuwaiti graduate students gathered in London to react to the crisis. They issued the first written statement denouncing the invasion, and they held a hastily organized march from the Kuwaiti Embassy to the nearby Iraqi Embassy, where a protest letter was delivered to the Embassy staff. The next day, these students formed the Kuwaiti High Committee to coordinate and oversee handling of the crisis. To no avail, street protests continued at the Iraqi Embassy daily for several days. To achieve restoration of Kuwait’s nationhood, the High Committee aimed to motivate all Kuwaitis in Britain and Ireland to work toward this end and to enlist British, Arab, and world public opinion to back their cause. As the crisis persisted, the High Committee created 19 subordinate committees with a combined total of nearly 200 members to carry out a multiplicity of functions including public relations, research, social activities, and assistance for Kuwaitis in need. Public relations efforts encompassed media monitoring, contact, and interviews; creation of literature in English and Arabic; participation in debates, political meetings, conferences, and TV news programs; and organization of such newsworthy events as ceremonies, marches, and rallies. The social activities aimed to create cohesion among Kuwaiti exiles and to boost morale. Despite a communications blackout in Kuwait, evidence of the FKC’s activities regularly reached and reassured the beleaguered population that they had not been forgotten and that hope for liberation was no pipe dream. Instrumental in facilitating the FKC’s work was the prior existence of the National Union of Kuwaiti Students. Its student administrators formed the High Committee, its headquarters in London became the FKC headquarters, and, due to NUKS, a structure was already in place for liaison with Kuwaiti campus activists throughout the UK and Ireland. A member of the British public, in a letter written 2 days after liberation, summed up the achievement of the FKC. |

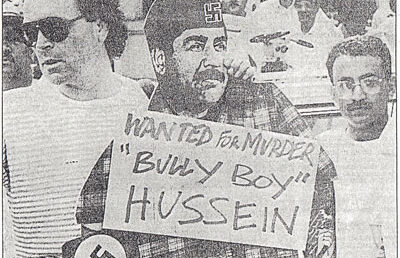

Invasion Protested in London

Kuwaiti protests at the Iraqi Embassy began on the afternoon of the invasion. On the evening of August 3, Michael Lorrigan (on left), with his cardboard Saddam effigy, left his home in Bristol and the next day and the day after joined Kuwaitis protesting at the Iraqi Embassy. By his 3rd day in London, Lorrigan discovered the nascent Media Committee and for the next 7 months became one of its most dedicated members. Lorrigan had previously worked in Kuwait for 8 years as a teacher and deputy headmaster. (Photo by George Jaworskyj, August 4, 1990, for the next day’s Sunday Times.)

| The Politics It took only days to realize Saddam Hussein never intended to leave Kuwait. Defying global condemnation, he declared Kuwait would soon become Iraq’s Province 19. Iraq was then the world’s 4th largest military power. Its troops began instantly fortifying Kuwait with millions of landmines and thousands of miles of trenches. Countless buildings were converted into machine gun nests and countless underground and pillbox bunkers were built. The oil wells were wired with incendiary explosives. As hope for a political solution faded, it became clear only military force could dislodge Iraqi troops from Kuwait. It was not unrealistic to fear such a war might last a long time and have a high body count. In this political climate, Britain’s far left parties took to the streets weekly to protest military intervention and to brand military action as a war about oil and not Iraqi aggression. The longer the occupation lasted, the more the danger grew that these ideas would spread from far left to soft left to center parties and lastly to the right. If the UK rejected armed force, how might it affect American public opinion? The FKC’s Media Committee recognized this potential for disaster and assumed the mission of countering it. The Media Committee became in this regard the heartbeat of the campaign to secure Kuwait’s freedom. The MC’s strategy was to seek constant news media attention and to keep the focus on Kuwaiti freedom and Iraqi brutality. Interviews were set up with journalists, debates were engaged in at major universities, meetings were arranged between Kuwaitis and British politicians, public speaking engagements were acquired for Kuwaitis representing the FKC, press releases were issued, and logistics were prepared for major marches. Support from the British public was also enlisted by creating the Friends of Kuwait, an organization run out of FKC headquarters. An agonizing issue for the MC was Saddam’s “ace” – holding foreign hostages as human shields. When he began releasing them in late autumn, MC members breathed a collective sigh of relief. Military action would no longer mean certain death for about 2,000 foreign civilians. Due to the British presence on the MC, Kuwaiti members were exposed to the policy of appeasement that haunted British history. They then used this reminder – the peril of appeasing a brutal dictator – to great effect in interviews and speeches and on literature and on placards. was typical. |

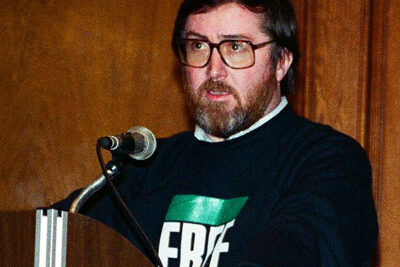

An “Out of the Gulf” Rally

Every weekend Britain’s anti-war activists, led by the Committee to Stop War in the Gulf, organized marches against military intervention on behalf of Kuwait. The Committee to Stop War in the Gulf was an umbrella group consisting of the Socialist Workers Party, most left-wing members of the Labour Party, various church organizations, many trade unions, the National Union of Students and local student unions, and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. They labeled possible intervention as oil driven and imperialistic, and favored giving the UN’s economic sanctions against Iraq time to pressure Saddam into a peaceful withdrawal from Kuwait. Their goal: spread anti-war sentiment across all political spectrums in the UK. The size of their marches continually grew, culminating in a huge rally at Trafalgar Square of 40,000 participants on January 12, 1991. Demonstrations were held in cities throughout the UK, including in Glasgow (shown here), and they continued after the Gulf War began. Despite the combined political might of these organizations, they were unable to prevent the British military from joining in the coalition forces or to garner enough public support to halt the war before a military defeat led Iraq to accept a ceasefire on March 3, 1991. (Photo and © by Derek Copland, Glasgow, February 1991. Reprinted with permission.)

| The Plight For Kuwaitis abroad, the stunning news of the Iraqi invasion produced a profound psychological shock. The Iraqi regime issued falsehoods to the international news media by claiming Kuwaitis invited the invaders in order to overthrow their Al-Sabah rulers. On August 8, Saddam announced Iraq’s intention to annex Kuwait permanently as Iraq’s 19th province. Each passing day brought new reports of Iraqi brutality and looting. Fears mounted for the safety of family and friends inside Kuwait. Added to the concern for loved ones and the anxiety over their new status as a people without a country was the everyday concern of subsistence. Some wealthy Kuwaitis had substantial investments outside their country, but most did not have the resources to cover a long unplanned absence from Kuwait. Gone were their homes, businesses, and, in many cases, bank accounts. Overnight their Kuwaiti dinars had become worthless. Iraqi dinars had replaced their currency. The Kuwaiti government and banks took immediate steps to ease this plight. While the invasion was in progress, both were already transferring funds out of Kuwait and both had for years invested funds abroad. To those families requiring financial aid, the Kuwaiti government wired into their bank accounts a monthly stipend to cover housing expenses. Those without bank accounts could pick up a check at an office set up by the Kuwaiti government. The National Bank of Kuwait set up temporary headquarters in London and offered a daily sum of £500 to its depositors during the first weeks after the invasion. This payout was again offered several times during the occupation. The London-based United Bank of Kuwait had enough liquidity to sustain losing about a third of its deposits within weeks after the invasion due to customer withdrawals. Because many Kuwaiti families and Kuwaiti students still remained in financial need, several FKC committees met their needs by assisting families in obtaining funds from Kuwaiti sources and in some cases directly distributing funds, by establishing a free medical clinic and recreational activities for children and adults, by publishing a guide to free British social services, and even by distributing newspapers for free. No fee was required to attend or participate in FKC events, whether it was a panel discussion, lecture, performance, or ceremony. In addition to organizational sources of aid, many Kuwaiti individuals helped families in need. Standing out among them were contributions from Abdulhameed Al-Sane and Sheikha Dr. Suad Al-Sabah. The latter also assumed the entire cost of several FKC activities. |

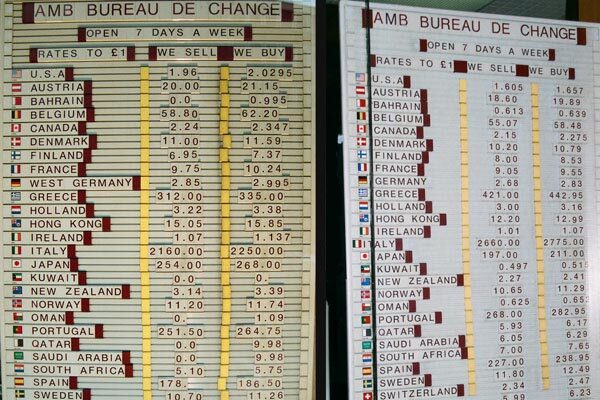

During and After

These 2 foreign exchange bureau listings, shown during the occupation (on left) and soon after, revealed the magnitude of the economic debacle caused by the invasion. After August 2, 1990, value of the Kuwaiti dinar, previously worth about £2 (US$3.50), sunk to zero. Both establishments were on Edgware Road in London. (The zero sale values for Gulf nation currencies in the photo on left were not due to the invasion. Many bureaux did not offer this service since residents of these nations brought money to the UK for conversion into pounds, but hardly ever converted pounds into their local currencies.)

| The Diwaniyas An integral part of Kuwait’s heritage, the diwaniya is a weekly gathering by men in a Kuwaiti home in a room set up for that purpose. It is an open house with newcomers welcome to join the host’s family and friends for an evening of conversation, refreshments, and occasionally viewing of TV or DVDs. The occasion is primarily social, but diwaniyas may also serve educational, business, and political purposes. To this end, guest speakers may be invited. Shortly after the invasion, a group of Kuwaitis from the London community formed the Kuwaiti People’s Committee with the main aim of conducting a daily diwaniya each night from 8 pm to midnight for exchanging news and discussing the crisis. The Committee rented a room on Dorset Square for this purpose. It had no chairman or formal membership. Some of the most frequent participators took turns acting as moderator at the meetings. Invited to speak at some of the KPC meetings were such prominent Kuwaitis as Sheikh Rashid Al-Hmoud Al-Sabah (the Emir’s envoy to the UAE), Cultural Attaché Ahmad Al-Duwaisan from London’s Kuwaiti Embassy, Dr. Mohamed Al-Rumaihi, Kuwaiti Minister of Planning Sulaiman Al-Mutawa, and politicians Jassim Al-Kharafi and Ahmad Al-Saadoun. Another Kuwaiti guest was a young man who had recently escaped from Kuwait and who offered a first-hand account of the distressing conditions in the occupied nation. Among the foreign visitors who graced the diwaniya were Egyptian author Fahmi Huwaidi and exiled Iraqi religious leaders who opposed Saddam’s regime. The KPC also engaged In other activities. It published the weekly newsletter Beladi [My Country]. It sponsored a meeting in Porchester Hall with Mr. Huwaidi as guest speaker and invited all interested parties to the event. It created a sports committee to train men several times a week with jogging and other outdoor exercise for possible military service, and it had volunteers with medical training available in case treatment was needed in the field. After liberation, in coordination with groups in 10 countries, former KPC members organized a Run for Freedom for petitioning the UN to help bring home The Missing. The race was held simultaneously in these nations on May 17, 1991. In mid-November 1990, the Social Committee of the Kuwaiti High Committee rented a building on George Street as a London Diwan. One room was for diwaniyas. Some of its distinguished guests included Kuwaiti Minister of Finance Sheikh Ali Al-Khalifa Al-Sabah, Kuwaiti Minister of Planning Sulaiman Al-Mutawa, and politician Jassim Al-Sager. During the tense days of the coalition force’s ground attack, Kuwaitis gathered around the TV in this building to stay apprised of the latest news. Kuwaitis stranded in other countries also set up diwaniyas. One example covered in this website are scenes from a diwaniya in Dubai. |

An Anxious Time

On the night of December 24, 1990, at the Kuwaiti People’s Committee daily diwaniya, the audience listened intently to guest speaker Ahmad Al-Saadoun describing how the coalition forces were preparing for battle. The possibility of a tremendous loss of life weighed on everyone’s mind.

| The Women Kuwait’s women played significant roles inside their country in resisting the Iraqi regime and outside their country in campaigning to end the occupation. They were a driving force in Kuwait’s liberation through their high level of participation on most FKC committees and in demonstrations and other events. That women were sometimes the standard-bearers in the major marches was symbolic of their commitment and activism. They also organized committees mainly or exclusively for women. Under the Kuwaiti High Committee’s auspices, the Women’s Committee was set up soon after the invasion to develop activities for women and children. On November 2, the Committee held a large exhibition to support Kuwaiti families in financial need mainly by selling women’s handicrafts, Kuwaiti collectibles, prepared foods, herbs, literature, and music tapes. The event included performances by girls, an art contest for children, a photo display, and refreshments. Well-known Kuwaitis took part as both sellers and buyers. Independent of this committee, Najla Al-Naqi issued the Sawt Al-Mar’a Kuwaitiyah [Voice of Kuwaiti Women] newsletter. From the Kuwaiti Embassy via satellite, she aided in broadcasting into Kuwait and in monitoring messages from Kuwait. These communications yielded valuable intelligence about the situation inside the homeland and helped comfort families with news of the whereabouts and welfare of loved ones. Al-Naqi also formed her own Kuwaiti Women’s Association to publicize the Kuwaiti cause through street marches and to raise funds for war victims through a charity bazaar. The Kuwaiti-British Friendship Committee was mainly for Kuwaiti women, but it had one key British male member, John Lewinton, who had been a hideaway in Kuwait. The idea for forming the K-BFC came from Seham Al-Marzouq, a member of the Kuwaiti High Committee and the Media Committee, and it was started and run by Mona Taleb and Amina Al-Mulaifi. Its purpose was contact with the families of British soldiers, sailors, and air force personnel deployed in the Gulf. K-BFC members enlightened families about the issues that their loved ones were being asked to fight for. After the British hideaways and hostages were released in mid-December, these ex-pats assisted this effort by describing conditions they had witnessed in Kuwait during the occupation. During and after the Gulf War, members visited the British wounded and attended memorial services in Glasgow and London. The K-BFC continued its work in Kuwait through the end of 1992. It sponsored visits to Kuwait each time of 100 British family members who had lost a relative in the Gulf War. The K-BFC disbanded when funding could not be obtained from the government or other sources. The K-BFC was also known as the BKFFA, British-Kuwaiti Forces & Families Association. Yet another significant service performed by FKC women was to go to Kuwait immediately after liberation to join the Red Crescent Society. |

Commemorating Britain’s War Dead

On March 2, 1991, the 3rd day after the coalition forces declared a ceasefire, members of the Kuwaiti-British Friendship Committee participated in a ceremony at the Cenotaph. To honor the 47 British lives lost in the war, Amina Al-Mulaifi (on right) and Najla Al-Naqi laid a wreath at the foot of the monument.

| Hideaways & Hostages Iraq’s sneak attack during the night of August 2 surprised not only Kuwaitis, but also thousands of foreigners in Kuwait. The largest group was British, followed by Bulgarians, French, Italians, Japanese, Germans, and Americans. The invasion also trapped citizens of most other European nations, Brazil, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, many for nearly 4 months. During the first days after the invasion, some foreigners fled across the border into Saudi Arabia. Helped by Kuwaiti resistance members, a handful managed to escape later. After Iraqi troops killed a British citizen on route to Saudi Arabia on August 11, the British government urged its citizens to hide rather than flee. On August 15, the Iraqi regime issued a list of nationals to be rounded up for human shields – British, French, Japanese, Germans, and Americans. Other nationals could move about, but not leave. During the ensuing months, partly due to visits to Baghdad by official and unofficial sources, about 2,600 foreigners were allowed to leave. Governments that had not committed to join the coalition forces had an easier time in rescuing their citizens. These various stages of release did not include about 1,500 adult British, Japanese, and American males who, as late as December, were still in hiding or who were being held in strategic locations in Kuwait and Iraq as human shield hostages. Many of those in hiding in Kuwait were sheltered in safe houses set up by ex-pat organizers or in the homes of Muslims of various nationalities. The ex-pat underground network and the Kuwaitis ensured a flow of food and information to the hideaways and were also able to smuggle out messages. The level of hardship varied with location, but one constant was the chill of hearing unfamiliar footsteps or an unexpected knock on the door. Some hideaways were captured due to complacency or betrayal. Some died in captivity. On December 6, after Iraq proclaimed all remaining foreign hostages would be released, the hideaways emerged and were able within a week to fly home via Baghdad. In Britain, many hideaways, hostages, and their families participated in FKC events as individuals or as part of their newly organized group Hostages of the Middle East (HOME). Their appearances on talk shows and at press conferences and their interviews by the news media helped rally British public support behind the use of military force to liberate Kuwait. They and their friends also became members of the FKC’s Friends of Kuwait. On January 13, they joined the large FKC march in London and carried signs that read “I Am Alive Thanks to Kuwaitis.” Books published about their experiences include John Levins’ Days of Fear, Tim Lewis’ Human Shield: British Hostages in the Gulf and the Work of the Gulf Support Group, and volume 1 of Paul Kennedy’s ebook trilogy The Lid Is Lifted. (Text adapted mainly from reminiscences of John Lewinton.) |

Eyewitness

On December 16, 1990, just days after being allowed to leave Kuwait, attorney Kevin Burke addressed a large assembly organized by the Kuwaiti People’s Committee. He reported on the suffering of the Kuwaiti people and the conduct of the Iraqi occupiers, but emphasized it was only a matter of time before Kuwait would be free again.

| The Rallies For those never having organized a rally, imagining the amount of work involved will be hard. Once the theme was agreed on, the day had to be chosen: weekday or weekend? The police always preferred Sundays because of light traffic. Once the date and time were agreed on, the route was discussed with the always cooperative and helpful Metropolitan Police. They approved of these marches, which whether vocal or silent were always peaceful, dignified, and well organized, and dubbed them the “designer rallies.” The next job was to print slogans for the posters. These had to be stapled to a board, which in turn was stapled to a long stick creating a sign strong enough to bear the London wind. The largest number of placards made was 4,000, which took over every inch of office space. Visitors must have wondered whether they were at a warehouse rather than an office. If balloons were to be released, they needed to be ordered and inflated. But first, with an effort requiring numerous faxes, permission had to be obtained from the British Civilian Aviation Authority. Then the rally had to be publicized by poster, leaflet, newspaper, and word of mouth. Radio and TV were not options as they forbade political ads. Inviting rally speakers had to be arranged at least a month in advance, especially if they were MPs. A press release was sent 5 days before the rally to all leading newspapers and radio and TV stations so the rally could be covered as news. They were reminded by phone the day before. PA systems had to be hired and set up. To supplement the police presence, FKC marshals had to be appointed and duties assigned. On the morning of a rally, volunteers packed the signs into the truck of FKC’s printer Sam Bassan. It was driven to the Kuwaiti Embassy, where all major rallies began. The marchers took whichever sign they wished to carry and mingled with long lost friends to catch up on the latest news of Kuwait. Police and marshals had little to do once the marchers began as they were so disciplined. All the marches were on cold dry days, some so cold that everyone was glad to keep moving. Each march was an intense emotional experience with young, old, handicapped, male, female, Kuwaiti, and non-Kuwaiti participating with equal passion. A wonderful feeling of unity pervaded the rallies, especially after the final speech when everyone sang the national anthem. There was always a feeling of relief at the end because everything had gone smoothly and the chilled marchers could now find relief from the cold British weather. But the work did not end there. The signs had to be reloaded into the truck and then unloaded and stored at the office – ready for the next rally. (Text adapted from Carolyn Tshering, Brief History of Free Kuwait, March 1991.) |

The FKC “Save the People” March

On January 13, 1991, thousands of Kuwaitis and supporters engaged in their final major march. It ended with a rally in Hyde Park and the release of 3,000 black balloons to symbolize the 300,000 people still suffering inside Kuwait.